DCS, CCR and PFO: a vignette

- Michael Mutter

- 18. Dez. 2025

- 5 Min. Lesezeit

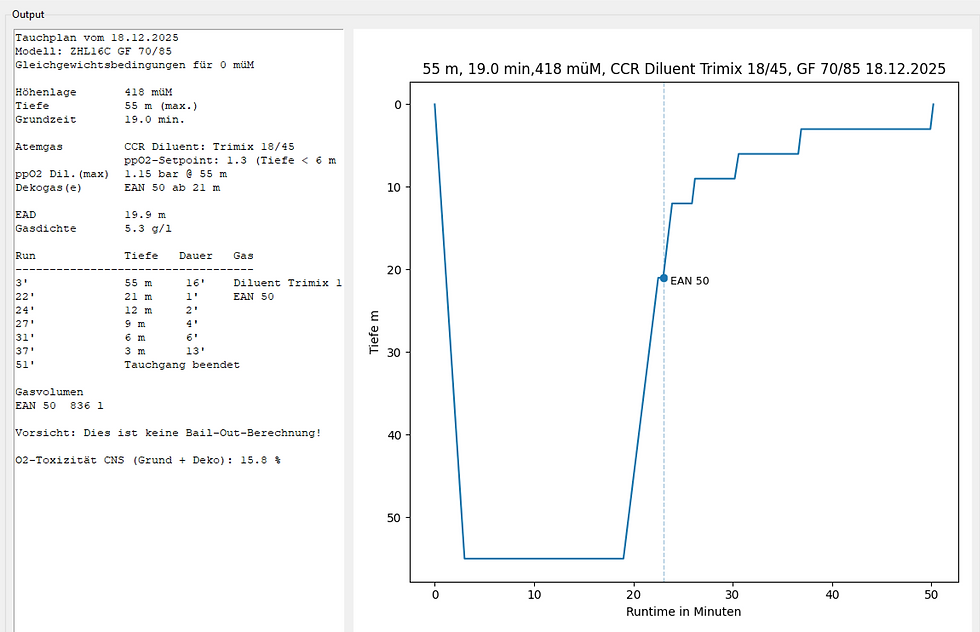

A 50-year-old diver went diving in a Swiss lake with his closed-circuit rebreather (CCR). The plan was to dive to a depth of around 55 meters with a bottom time of approximately 20 minutes (time until leaving the depth). Compressed air was used as the diluent, at a constant oxygen partial pressure of 1.3 bar. The last decompression stop was at 6 meters.

The diver complied with all decompression requirements and ended the dive after a total of 54 minutes. However, about 30 minutes after surfacing, he suddenly experienced severe vertigo. His diving partners reacted correctly and immediately alerted the emergency services. The diver was transferred to a hyperbaric chamber for hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

After the third chamber session, the symptoms disappeared completely. After a total of six pressure chamber sessions, the diver was discharged home without any complaints. Further examination revealed a patent foramen ovale (PFO). Interventional closure was recommended, but the diver refused—he does not want any heart surgery. He wants to continue diving with his rebreather.

What exactly happened, and what advice should he be given?

Diagnosis: Inner ear decompression syndrome (IEDCS)

The hyperbaric physicians treating the patient diagnosed inner ear decompression syndrome (IEDCS). The inner ear is considered to be particularly sensitive to gas bubbles. As with all forms of decompression syndrome, symptoms typically occur after diving, usually within the first 30 minutes – when tissue supersaturation is at its highest.

There is a close connection between IEDCS and the presence of a patent foramen ovale. If gas bubbles enter the arterial circulation from the venous circulation, they can shrink on their journey to the organs and thus become harmless. However, if this journey is short – as is the case with a PFO – the bubbles reach a target organ such as the inner ear more quickly.

There, due to the special anatomical and physiological characteristics, they encounter a compartment that is highly supersaturated with inert gas. This supersaturation promotes renewed growth of the bubbles and thus the development of an IEDCS.

Why does a PFO increase the risk?

The risk associated with this mechanism increases primarily:

with increasing depth and length of the dive

and with shorter transit time of the bubbles in the arterial blood.

Deep dives with an existing PFO are therefore associated with a particularly high risk of IEDCS. Accordingly, PFO is considered an independent risk factor for this specific form of decompression syndrome. (More about IEDCS here.)

Does the PFO need to be closed?

The short answer is: No, not necessarily.

The real problem is not the PFO itself, but the gas bubbles. If you reduce their formation through appropriate strategies, you can significantly lower the risk of DCS – even with an existing PFO. For this reason, a recent position paper does not generally recommend PFO closure even after suffering from DCS.

Recommendations for divers with PFO

(abridged, according to SUHMS guidelines)

Divers with known PFO should take special precautions:

Only one dive per day

Avoid cold temperatures and dehydration

No exertion and no pressing maneuvers at the end of the dive:

Avoid physical work underwater and currents

Remove equipment in the water and have it lifted out

Effortless exit onto land or into the boat

No carrying heavy equipment

No later than 30 minutes after a deep, long dive: only relax

Absolute diving ban in case of colds, as coughing or sneezing can promote the passage of bubbles through a PFO

“Only dive with helium” – sensible or not?

Since the diver refuses to use a PFO closure, he sought advice from experienced colleagues. Their recommendation: only dive with helium in future – meaning trimix. But is that really sensible?

In the Bühlmann model, helium has a half-life 2.65 times shorter than nitrogen. This means that tissues saturate more quickly and can exceed their supersaturation tolerance earlier. The result is longer and earlier decompression obligations – the so-called helium penalty.

From a purely decompression point of view, helium is therefore a disadvantage at first. Nevertheless, the recommendation is correct: compressed air is unsuitable as a diluent at a depth of 55 meters. The partial pressure of nitrogen there is over 5 bar, combined with a considerable risk of nitrogen narcosis and a very high gas density of around 8.2 g/l. This significantly exceeds both the recommended upper limit of 5.2 g/l and the absolute limit of 6.2 g/l. Compressed air has no place at this depth. The dive must be carried out with trimix.

The solution: gas change during ascent

A standard gas suitable for this depth is recommended, for example Trimix 18/45 as a diluent. However, it is not only the diluent that is crucial, but also the gas change during the ascent.

At a depth of around 20 meters, it is advisable to switch from CCR to a decompression gas, such as EAN 50. This abruptly reduces the partial pressure of helium being breathed to zero. The driving force for helium desaturation – the partial pressure difference between tissue and alveoli – is suddenly maximized. From this point on, maximum helium desaturation begins.

Since nitrogen has a significantly longer half-life, this advantage is only minimally reduced by the higher nitrogen content in the decompression gas. The diver thus specifically takes advantage of the effect of replacing a “fast” gas (helium) with a “slow” gas (nitrogen). This accelerates desaturation and reduces the supersaturation that is crucial for bubble formation more quickly than if diving continues with trimix.

This has a direct effect on the decompression profile and thus on the risk of decompression sickness (see the decompression profiles in the Dekoplaner © Michael Mutter). Although trimix causes faster saturation at depth, the targeted gas change during the ascent leads to more favorable desaturation overall. In practice, this corresponds to a time saving of several minutes in decompression obligations.

If the diver foregoes this time saving and instead remains in the water for the same amount of time as in a comparable dive with compressed air, this results in an immediate and relevant reduction in the risk of DCS. Additional safety can be gained by further extending the stops to 6 or 3 meters or by using an additional decompression gas, for example 100% oxygen at 6 meters – measures that are expressly recommended for divers.

Conclusion

Even after this severe case of decompression sickness, PFO closure is not absolutely necessary. Instead, the patient should be advised to take a series of measures:

strict adherence to the rules of conduct for divers with PFO, especially when surfacing and in the early phase after the dive,

as well as correct gas selection with targeted gas exchange to maximize desaturation during decompression and reduce supersaturation as quickly as possible.

This significantly reduces the risk of recurrent decompression syndrome – even without interventions on the heart.

Kommentare